How to write research papers that get published

This is the guide I wish I had when I stepped into the world of research and publishing.

If you've stumbled upon this article, my best guess is that you are looking for a guide of sorts to getting your first manuscript off your head, onto paper and finally into print. This blog is your guide to just that. I have tried my best to make it the set of rules, tips and tricks that I wish I knew when I wanted to publish my first manuscript.

Disclaimer:

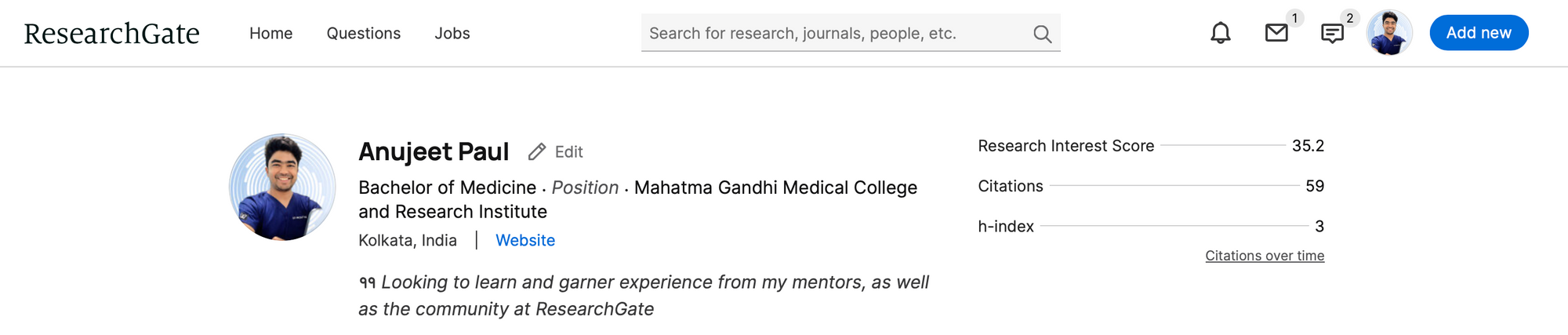

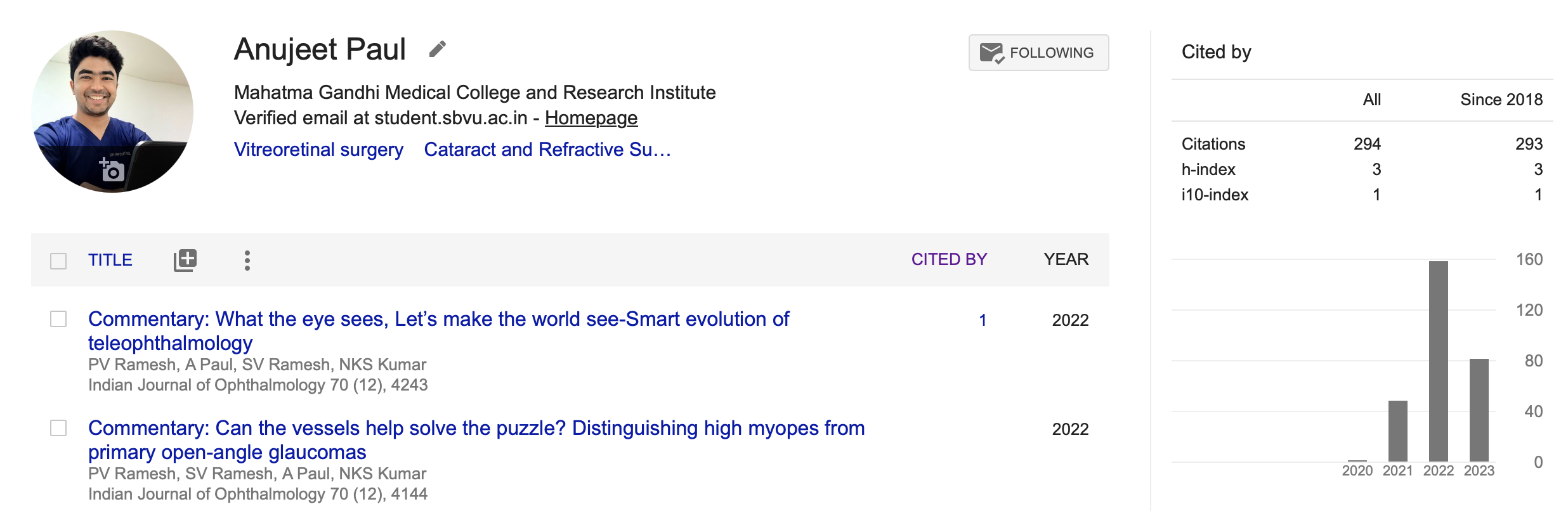

I am no expert. However, over the last two years, I have published 20+ manuscripts (15+ as either first or corresponding author), all in national/international, indexed, peer-reviewed journals. Barring my first two, all the remaining have been my brainchild and I feel I have some value to provide to those dipping their feet into research. There are plenty of experts who delve into the details of research methodology. However, there is no guide as to how to practically apply them.

I will provide links wherever I feel it is a genuinely helpful resource. All links will be summarised at the end as well. I will hand-pick all the areas you might get stuck in, due to lack of exposure, and lack of direction and provide effective workarounds. Lastly, I will share my own workflow and patterns that have worked for me in this regard.

You can click here to see the manuscripts published by me.

This guide will be particularly helpful if:

- You want to start publishing but you don't know where to begin.

- You have written your first manuscript but you don't know if it deserves a publication.

- You have published your first manuscript and now you don’t know what to do next.

- You're stuck because you're either technologically challenged, not getting the hang of review of literature or you cannot figure out if your manuscript will add anything to the existing literature pool.

Why should I even consider publishing?

Excellent question! There are a few reasons I personally feel one should consider publishing.

1. Lay of the land

You cannot publish without adequate groundwork in your chosen subject or field. This groundwork that you put in will give you a formidable idea about not only recent advances but also current concepts and preferred practice patterns in the field. YES, much more than a textbook can ever give you.

2. An incentive to read

As medical students, we love to crib about how a disease or a system just goes on and on in some textbooks. This is where a review article comes in handy. A narrative review summarises decades of research into a palatable 3000 words or so.

3. Being visible

Make your mark in your field. A publication permanently adds your name to an enormous literature pool. You become searchable and your work gets worldwide acknowledgement.

4. Build your portfolio

In a way, the world of research has been gamified. Websites like ResearchGate, Publons and Google Scholar attempt to quantify work done and keep universal track of metrics like citations. Often a link to your profile on this website acts like your own mini-portfolio.

Advantages of having a research-oriented mindset

Research humbles you. When delving into the details of any disease or therapy, you realise the amount you don't know. In this process, you shake off that superiority complex. Though the simplest solution is probably the correct one in medicine, research keeps you open to possibilities. It allows you to support the decisions you make on the clinical floor, thus boosting your confidence in diagnosis and treatment.

Disadvantages of having a research-oriented mindset

The world of statistics, pen and paper is vastly different from the real world. No two patients are the same. The same drug for the same disease may produce a wildly different result that papers cannot account for because it may even be a one-in-million outcome. A research-dominated mindset has been shown to reduce risk-taking behaviour of a practitioner, maybe even suppressing his/her gut feeling or his/her sixth sense to treat a disease, relying heavily on statistics and data.

Where can I publish?

With all this out of the way, let’s get right into it.

So the idea is to show your work. You pick a journal for publishing. All journals have their own worth. Some may be online-only, while others may be quarterly or biannually published.

However, you are looking for certain specific criterias in a journal to deem it worth sending your manuscript to. There are:

- Indexed

- Peer-reviewed

- Impact Factor

Ideally, you want to publish in a physically published, peer-reviewed, indexed, state, national or international journal with a high Impact Factor. However, this is the ideal scenario. Obviously, it goes without saying your first publication may not meet all these criteria and that is okay. However, if there is a singular criteria I was told to recommend I would urge you to choose a peer-reviewed journal at the least!

There are numerous sources that will explain these criteria. This source is the most lucid one of them all.

What can I publish?

There are a variety of manuscripts to choose from. Broadly, these are:

- Meta-analysis and systematic reviews

- Original studies

- Case-reports and case-series

- Photo-essay / Images of interest

- Letter to Editor

- Miscellaneous - Surgical techniques, Point-counterpoints etc.

However, making the assumption that you are a beginner at this, I will try to help make your approach as lucid as possible. In my opinion, everyone should start with an attempt at a case report and an original article. Here’s why:

Why publish a case report?

- As a beginner, a case report gives you just the right amount of exposure to the world of publishing to decide whether you enjoy it or not. Though it requires an attempt at a thorough review of the literature (ROL), only 10 references are needed for the final manuscript (give or take). This saves the process from becoming too overwhelming.

- The final manuscript involves writing a good case presentation (which is anyway a requirement for final post-graduate exams) as well as a cohesive discussion - stating your case and debating its relevance all in about 1000-1500 words.

Why publish an original article?

- An original article is the holy grail of research. You set up a research question or hypothesis and conduct a study. Finally, you must conclude by answering your research question or proving/disproving your hypothesis.

- Original articles are much more extensive (at 3000 words) and more time-consuming (extensive ROL). However, your research remains more wholesome.

What do I need to get started with publishing?

1. A bare-bones knowledge of the terminologies

Below is a comprehensive look at everything you will need to get started with a case report.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3894019/

https://www.eophtha.com/posts/how-to-write-a-case-report

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4404856/

https://www.slideshare.net/maheswarijaikumar/basic-research-terminologies

https://www.mckendree.edu/academics/research/irb/terms.php

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.708380/full

2. Tools

Fortunately, the 21st century has made life easier in this regard.

2.1 Searching and browsing

You will need a browser with an efficient bookmarking system. This is important because your search will lead to numerous open tabs. Selecting the appropriate links to bookmark will definitely make your work easier since you may always need to return to them at a later time.

My suggestion for this is Google Chrome (though I am comfortable with Safari, out of habit). Chrome is compatible with every single extension that you may need and that I will mention below.

2.2 Referencing

The facts stated in your manuscript need to be referenced. A number of digital reference managers are available. Personally, I feel all of them are sub-par in some aspect or the other when it comes to being a robust reference manager. However the following are my order of recommendations:

- Mendeley (Windows/MacOS): This is the software I use. It has its flaws, especially when it comes to citing correct sources and the cloud storage system is weak. However, it has its own in-built browser too.

- Zotero (Windows/MacOS): Comparable to Mendeley, in almost every aspect, however, it lacks its own browser extension. It has an inferior display UI and is quite buggy.

- EndNote (Windows/MacOS): This software is paid, albeit a one-time payment is required.

2.3 Writing your manuscript

You may choose any notepad software for your initial draft, however, your best software to get work done is Microsoft Word (2007 or higher). If you are working on a manuscript with multiple authors and you’re comfortable with cloud storage, you may look into Google Docs, though for referencing you’ll have to scoot back to Microsoft Word.

It would be prudent to download the extension for Zotero, Mendeley and EndNote for Microsoft Word as well for your browser.

3. Framing the exoskeleton

Often, throughout the course of your literature search or manuscript writing phase, the results of other studies will tend to throw you off track. It is important to be very clear about your aims and objectives from the get-go. Do not lose the forest from the trees.

For a case report: You are bringing to light a rare entity or association. Sometimes it may be unique management as well. A few pointers you must always be clear while framing your exoskeleton in this regard should be:

- The degree of rarity: Whether this is the first time something has been reported, or is it rare for a certain demography/population. Adequate literature in support of the same.

- Confirmation of diagnosis: Even though a feature or characteristic is clinically evident or implied, for a research publication it must be proved (with the investigation modality of choice for that diagnosis) For example It was easy for clinicians to diagnose fungal sinusitis during the second wave of COVID by clinical features alone and start the patient on Amphotericin B. However to publish the same, one needs a tissue diagnosis of Mucormycosis for it to be acceptable for publication.

For an original study: The objective, in this case, is to either provide/disprove a hypothesis or answer a research question. A few pointers for framing your exoskeleton in this regard would be:

- Clearly state your aim for the study. The entire study once started will be focused on reaching this aim.

- List out some secondary objectives. Alongside the aim, you can look to study this too (owing to the fact that you may be collecting information relevant to deriving a conclusion for this)

- Set robust criteria for inclusion or exclusion for your study. This is important to eliminate any bias within the study.

- Calculate your sample size.

4. Storytelling is a virtue

I feel it is at this point, you have the facts (sometimes irrelevant ones as well) and what is left is, knitting the story together. Expect to have multiple drafts, especially if you have mutiple authors weighing in, because they will bring in other viewpoints that you may have not thought of.

Here are a few key points that I have inculcated:

- Start your story as close to the end as possible. This is the single most important tip I can provide. A lot of irrelevant examinations, tests and investigations are done on the floor. There is no need of elaborating them. It helps to summarise blood/ tissue investigations and imagining in their own paragraphs and in the order they are usually expected. You are expected to present the findings in chronological order. Finally, the key findings should be apparent through your nature of writing.

- The discussion is meant for analyzing and interpreting all the clues and possibilities. Quoting other authors and their findings only works if you want to support yours or refute this. Never quote as a passing statement to make your manuscript more voluminous.

- A good discussion is one of whether you also cite literature that did not agree with your findings and outcome. Here you are also at liberty to hypothesize and postulate why your outcome is so.

- Your conclusion should effectively answer the main question or dilemma stated by your in your introduction (in a case report) or purpose (in an original article).

Statistics and Data Collection

Data collection is an art, not a science

This is by far the most sketchy area and the part that will frustrate you the most!

I will tell you why.

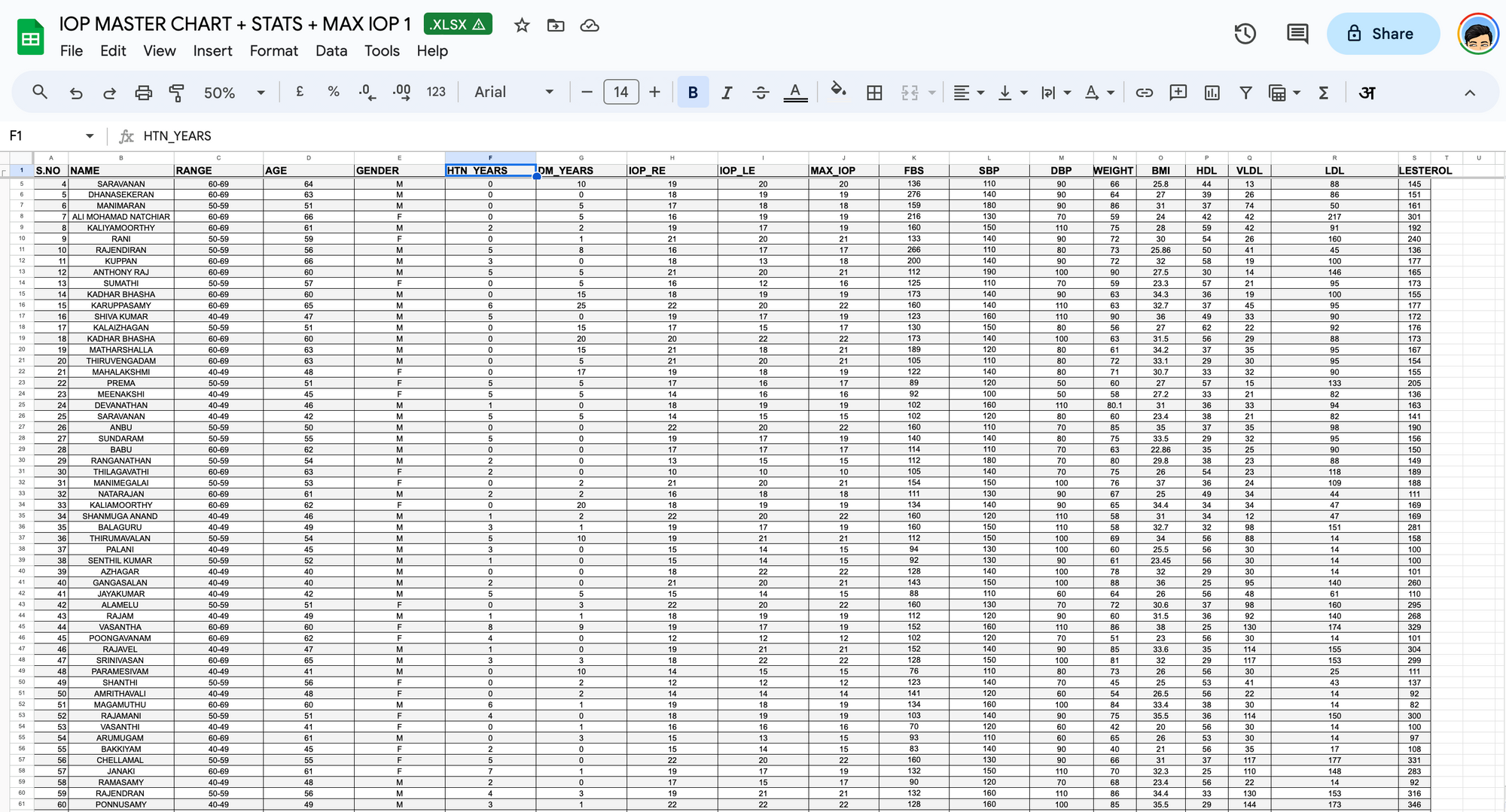

If you’ve attempted an original study you’re well aware that once it begins, as the junior-most person on the research team, you have to prepare an infamous ‘master chart.’ A master chart is a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet containing every documented value/finding for every patient in a study. Needless to say, it can get extremely long and confusing.

This is what it may look like.

Here are a few useful pro tips that may be useful in this regard:

- Collect any information that may be remotely relevant.

- Make use of the multiple sheets feature in the lower corner of Microsoft Excel. Sheet 1 may be the master chat with ALL the information. Sheet 2 may be used to copy only the relevant columns. Therefore, when you finally sit to assess your master chart, you can use Sheet 2 to figure out what you want to calculate.

- Collect information in the form of numerals. Assign numbers to alpha-numeric data and a key to what they may stand for.

The Discussion!

This is really the make-it-or-break-it portion of your article. The third act of the movie is where you are in the director’s seat.

In this section, your objective is to state your findings and compare them to the existing literature. You must remark whether your findings are in agreement or disagreement with previously similar studies or reports. Alongside, you may postulate why there is a difference as well as why your study may be giving out the outcome that it is. It is really easy to lose the forest from the trees during this segment of the manuscript but it is imperative that you keep your content relevant and crisp. For an original article, you may mention the limitations of your study, a take-home message or what may be studied in the future.

Submitting

If you’ve made it here, you’ve already done a great job!

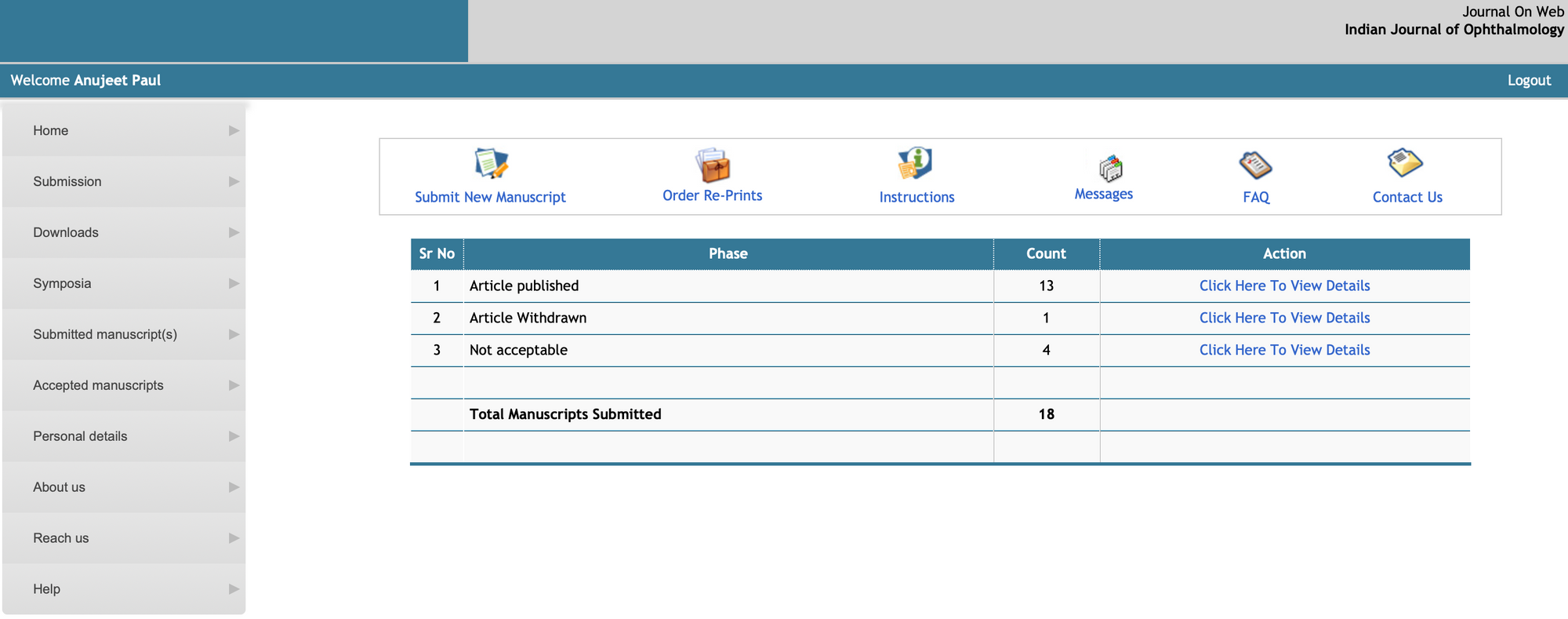

Manuscripts are submitted on the online portal of the journal. Before submitting you would have to make yourself an account on the journal’s website.

However, before submitting please do a thorough spelling and grammar check on your manuscript. Though the word limit and procedure to submit are nearly identical for most journals, it is a good practice to still head over to the “Instructions to Authors” section of the journal and check out what the guidelines for your submission would be. It would be a fairly simple procedure once you go through it.

Ideally, you would need:

- A Microsoft Word document with your entire manuscript along with the abstract (structured for original articles and unstructured for case report/series) in the font and size mentioned by the journal (usually font size 12, Arial or Times New Roman with double spacing). References should be in Vancouver superscript.

- High-quality photo(s) should you decide to submit any. Photos should be cited in the manuscript and legends should accompany the photos.

- A copyright form - a form stating that that work submitted by you is your original work (readymade form would be available from the journal website)

- Annexure documents: questionnaires etc.

Pictures tell us a thousand words

Not everything is a case report, case series or original article

I have added this section in because often we forget that many journals accept interesting photos of clinical relevance in the form of a standalone image with a paragraph of text or even a photo-essay. These are also publications and are much easier to work on.

You may attempt these if:

- It is your first attempt at writing a manuscript and you are quite confused on how to begin.

- You’re not finding the time to sit with an entire case report/original article.

Rejection need not be a bitter pill to swallow

One bitten, twice shy?

Replies from the editor of a journal typically take 2-6 months. The reply can be in the form of a revision which the journal is requesting the author to make to the manuscript following which it will consider the manuscript once again for publication or a rejection. Of course, a reply can be a direct acceptance as well too!

If your manuscript is rejected, there is no need to panic! Often, they are rejected with a set of comments from the reviewer, so that you can make the changes and consider re-sending them to another journal. Rejection may also stem from not choosing the correct journal for publication. For example, certain journals accept only case-based scenarios while your manuscript is a community survey. Or, the journal focuses only on recent advances while your manuscript isn’t one.

My two cents on rejection would be:

- Go through the rejection mail in detail. Read the comments from the reviewers carefully.

- Some of the comments may be prudent to address right away and you may make the corrections to your manuscript.

- Send it to the next journal of your choice the very next day.

Concluding remarks

I could go on and on, on how to write a manuscript, because there is no end to this. However, I believe this basic introduction is enough to sow the seeds for a research oriented future.

My inbox is always open!